On the Way of Resilience With the Baobabs

by Tahina Roland Frédéric

[La version française est ci-dessous]

Crammed into the local bush taxi, a “Renault Super Goélette”, we head northwards along the National Road N°8. We travel through seemingly endless, desolate countryside. In the oppressive heat, we open a window and a cloud of red dust fills the car. A grueling four hours and 80km stint sees us finally arriving at our destination, Lambokely. Here, we are enchanted by a picture postcard-perfect landscape, in which the village appears painted against a mesmerizing backdrop of “Baobab forest”.

Lambokely village is located in the Menabe-Antimena Protected Area of central-western Madagascar. Off the south-eastern coast of Africa, Madagascar is the largest island in the Indian Ocean. The village was established fairly recently and its expansion has been astonishing. Its creation can be linked to recent waves of migrants coming from the far south of Madagascar. To escape severe drought and famine there, these communities have been fleeing the arid south and settling in the Menabe-Antimena area, in hopes of finding somewhat more fertile land and securing work.

On my arrival, I am warmly welcomed by community ranger Bendray Zoemana, a leader of his village's community patrol team. In 2020, Bendray was recognized as a "conservation hero" by the US Ambassador. He proudly shows me his honorific certificate, signed by the Ambassador and neatly displayed on the wall of his hut. Bendray is an old friend, with whom I worked on a project aimed at strengthening the community patrol system in the Menabe-Antimena protected forest.

I keep talking to Bendray about the “Baobab forest" that I have seen, so that he suggests guiding me through it without further delay. But the closer we get to it, the more I am realizing that what I thought was a forest, is actually not that at all. It is merely a group of Baobabs widely distanced from each-other. Bendray tells me that less than 10 years ago, there was a healthy dry forest with various trees and other plants thriving between the Baobabs. These majestic "bottle trees" are the sole survivors: the forest was burnt to make way for slash and burnt agriculture. The Baobabs are still standing because their waterlogged trunks enabled them to withstand repetitive fires. They remain there, marked by the stigmata of the fires because the farmers did not bother to cut them. Bendray explains that in this dry forest, lived many endemic species such as Madame Berthe's mouse lemur, the Flat-tailed tortoise, the Giant jumping rat and the Narrow-striped mongoose. These flagship species are currently classified as either Endangered or Critically Endangered, on the Global Red List of Threatened Species-IUCN.

After 20 minutes, we arrived at the Baobabs. Their enormity leaves a lasting impression. While walking among them, I feel as if I am in a "natural cathedral" of sorts, their huge trunks making me think of columns that connect the earth with the sky. I draw Bendray's attention to the fact that among the 8 species of baobabs which exist in the world, 6 of them are endemic to Madagascar. They are therefore unique and they are a natural treasure for Madagascar - indeed for all humanity. Unfortunately some of these Baobabs also appear in the aforementioned IUCN red list.

After admiring and studying the branches of the Baobabs - which make one think of roots - my gaze turns to the ground. The soil is almost bare; it is arid and sandy. I recognize some dry residues from the crops of the previous season and from the remains of burnt trees from the original forest. While making a small hole in the ground to trying to observe soil structure, I shared my thought with Bendray: "Do you know that we have a lot to learn from these Baobabs? Imagine if these baobabs also had feet, what they would do if they saw forest fires raging in their area? ". Bendray looks at me with sparkling eyes. He understood what I meant. I continue: ‘If these Baobabs had feet, they also would have migrated like our grandparents and the majority of the village inhabitants. But these giants do not have feet and despite the degradation of their ecosystem and the pressures they face, they have survived until now. These baobabs show resilience. We, the local community, also have to be resilient in order to survive - the solution is up to us, because it is under our feet. I continue by pointing out to Bendray that, concerned about the drastic situation playing out in this region, resilience is the reason of my presence here. My stay at Lambokely is a preliminary assessment of the environment as part of an initiative called Taniala Regenerative Camp. “Taniala" is a combination of two Malagasy words, "tany" which refers to both “the soil" and "the earth" and "ala" which means "the forest".

Slash-and-burn cultivation continues unabated in Lambokely area. From August to November especially, illegal clearing and forest fires are rampant. Those involved in conservation of Menabe-Antimena’s protected forest are working very hard and are stepping up efforts to mitigate the ongoing damage. However, the future of this dry forest remains uncertain given the socio-economic effects of the Covid19 crisis coupled with climate change. In the region, the weather is increasingly unpredictable, the rains are irregular and weak and temperatures are rising. These effects are likely to worsen with unceasing land degradation. Consequently the stability of the local communities who migrated here, is once again under threat.

In this scenario, Taniala Regenerative Camp wants to be proactive and it aims to help people to break the vicious circle of deforestation-desertification-migration-deforestation by strengthening the resilience of local communities and also that of the ecosystem they live in. We plan to set up a base camp to showcase regenerative agricultural practices around Lambokely village. The Taniala Regenerative Camp initiative will connect local communities with practitioners, scientists and others involved in landscape restoration. The approach adopted is inspired by permaculture-design: it integrates agroecology, agroforestry, rainwater harvesting and ecological restoration practices. I present these concepts to Bendray and his friends, explaining that it is essential to consider the forest as a model. The natural forest produces large trees and food plants without any need of watering, fertilizers, or pesticide treatments. Its soil is always covered; made up of a mixture of trees and other plants. It shelters abundant biodiversity. Our production system has to be modeled on the forest. Resilience means reconciling agricultural production with ecosystem regeneration.

This approach allows us to work at different scales, ranging from a garden to an entire landscape, including farmland and community area. We started to install two permaculture gardens in Bendray and another in a friend’s yard. We knew that permaculture conveys a culture of permanence. Through the permanent beds of these permagardens, we can instill this culture of permanence among these local communities with a migratory background. Additionally, forest functioning is replicated in a smaller scale through these beds of permagardens. Bendray and his friends have watched and are learning from it. They understand the importance of organic matter or humus for the soil which is achieved through mulching. By combining crops, they are aware of the importance of biodiversity for resilience and they learn to optimize available space. They were also introduced to using of nitrogen fixating plants to enrich and improve their soil.

Currently our nursery is ready to produce different species of fruit trees and nitrogen-fixing trees which we will integrate into the local agricultural system and for our future food forests. Trees are not our enemy that have to be cut down - they are our ally. They nurture the soil and feed us people.

Local actions on the ground such as these, need to be encouraged and further developed within the global movement for ecosystem restoration. The proximity of these actions gives them the quality of catalyst for sustainable behavior change within communities. A quote from anthropologist Margaret Mead comes to mind: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has".

Finally, perhaps you would like to know a little about me. I am Tahina Roland Frédéric, a young Malagasy agronomist and forester who is promoting the Taniala Regenerative Camp initiative. My slogan is “Community and Living Soil”. Soil is at the very heart of our initiative because it is "the solution under our feet". It is simply the "SOIL-ution" for humanity.

Sur Le Chemin de la Résilience Avec Les Baobabs

Entassés dans une Renault Super Goélette, le taxi-brousse local, nous empruntons la Route Nationale N°8 en direction du nord. Sur notre trajet, un paysage de désolation s’offre à nous. Sous la chaleur accablante, nous avons ouvert les vitres et la poussière rouge s'engouffre dans l'habitacle. Après 80 km et 4 longues heures de route, nous arrivons à Lambokely, ma destination. J’ai sous les yeux un paysage de carte postale où le village semble être peint sur un fond de « forêt de baobabs».

Lambokely est un village de l'aire protégée Menabe-Antimena située au Moyen-Ouest de Madagascar, la plus grande île de l’Océan Indien, au large de la côte sud-est de l'Afrique. Ce village a vu le jour récemment et son expansion a été fulgurante. En effet, Lambokely est un village d’accueil, sa création est liée aux récentes vagues de migration interne des communautés venant de l’extrême Sud de Madagascar. Ces communautés fuient leur village d’origine à cause de la sécheresse et de la famine qui l'accompagne. Ils arrivent dans la zone Menabe-Antimena à la recherche de terres fertiles et de travail.

A mon arrivée, je suis accueilli par Bendray. Bendray Zoemana est un « ranger », il est le leader de l’équipe de patrouille communautaire de son village. En 2020, Bendray a été reconnu « héros de la conservation » par l’Ambassadeur des USA à Madagascar. Il me montre fièrement le certificat de félicitations qu’il a reçu, signé par l’ambassadeur, soigneusement accroché au mur de sa cabane. Bendray est un ami de longue date avec qui j'ai travaillé dans un projet de renforcement du système de patrouille communautaire dans la forêt protégée de Menabe-Antimena.

Je ne cesse de lui parler de « la forêt de baobabs » que j'ai vue, si bien qu'il me propose de me la faire découvrir sans plus attendre. Nous voici en route. Plus nous nous approchons, plus je me rends compte que ce que j'ai pensé être une forêt n'en est pas une. Il ne s'agit que d'un groupement de baobabs très éloignés les uns des autres. Bendray m’apprend qu’il y a moins de 10 ans, il y avait une véritable forêt sèche avec divers arbres et d'autres végétaux qui poussaient entre les baobabs et que ces « arbres bouteilles » sont les seuls survivants. La forêt a été brûlée pour faire place à l’agriculture. Ces baobabs en sont les seuls survivants car leur tronc gorgé d'eau leur a permis de résister aux feux répétitifs. Ils restent debout, marqués par les stigmates des feux car les paysans n'ont pas pris la peine de les couper. Bendray m'explique que dans cette forêt sèche vivaient de nombreux animaux endémiques tels que le microcèbe de Madame Berthe, la tortue à queue plate, le rat sauteur géant et la mangouste à rayures étroites. Ces espèces sont actuellement classées sur la liste rouge mondiale des espèces menacées de l’IUCN.

Nous voici maintenant près des baobabs. Ils me paraissent immenses. En marchant au milieu d'eux, j'ai l’impression d'être dans une "cathédrale naturelle", leurs troncs immenses et solides me font penser à des colonnes qui relient la terre et le ciel. J'attire l'attention de Bendray sur le fait que sur les 8 espèces de baobabs qui existent dans le monde, 6 sont endémiques de Madagascar. Ils sont donc uniques et représentent un trésor naturel pour Madagascar et pour toute l'humanité. Malheureusement, certains de ces baobabs figurent eux-aussi sur la liste IUCN.

Après avoir longuement admiré les branches des baobabs qui font penser à des racines, mon regard se tourne vers le sol. Un sol presque nu, aride et sableux, sur lequel je peux reconnaitre quelques résidus secs des cultures de la saison précédente et des vestiges d’arbres brûlés de l’ancienne forêt. En faisant un petit trou dans le sol pour tenter d’observer sa structure, je fais part de ma pensée à Bendray : « Sais-tu que nous avons beaucoup à apprendre de ces baobabs ? Imagine que les baobabs aient eux-aussi des pieds, qu’auraient-ils faits en voyant les défrichements et feux de forêt sévissant sur leur zone? ». Bendray me regarde avec des yeux pétillants, il a compris à quoi je faisais allusion. Je poursuis en précisant que si ces baobabs avaient des pieds, ils auraient migré eux-aussi tout comme nos grands-parents et la majorité des habitants du village. Mais ces géants n'ont pas de pieds et malgré la dégradation de leur écosystème et les pressions qu’ils subissent, ils survivent, pour le moment. Ces baobabs font donc preuve de résilience. Nous aussi, communauté locale, nous sommes amenés à être résilients pour survivre, la solution est à notre portée car elle est sous nos pieds. J’explique ensuite à Bendray que, soucieux de la situation alarmante régnant dans la région, la résilience est la raison de ma présence en ce lieu. En effet mon séjour à Lambokely est une descente préliminaire d’imprégnation et diagnostic du milieu dans le cadre d'une initiative appelée Taniala Regenerative Camp.

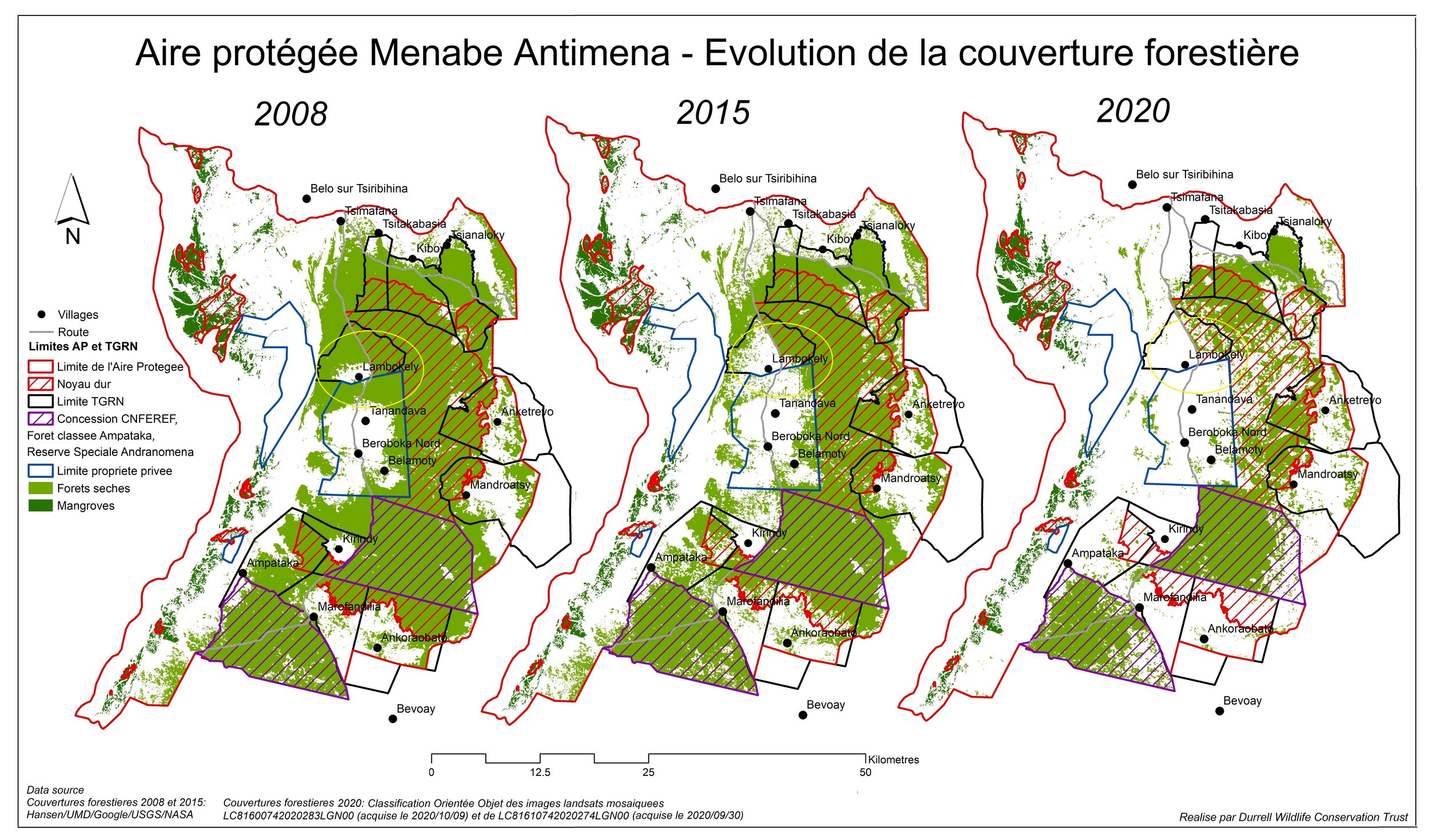

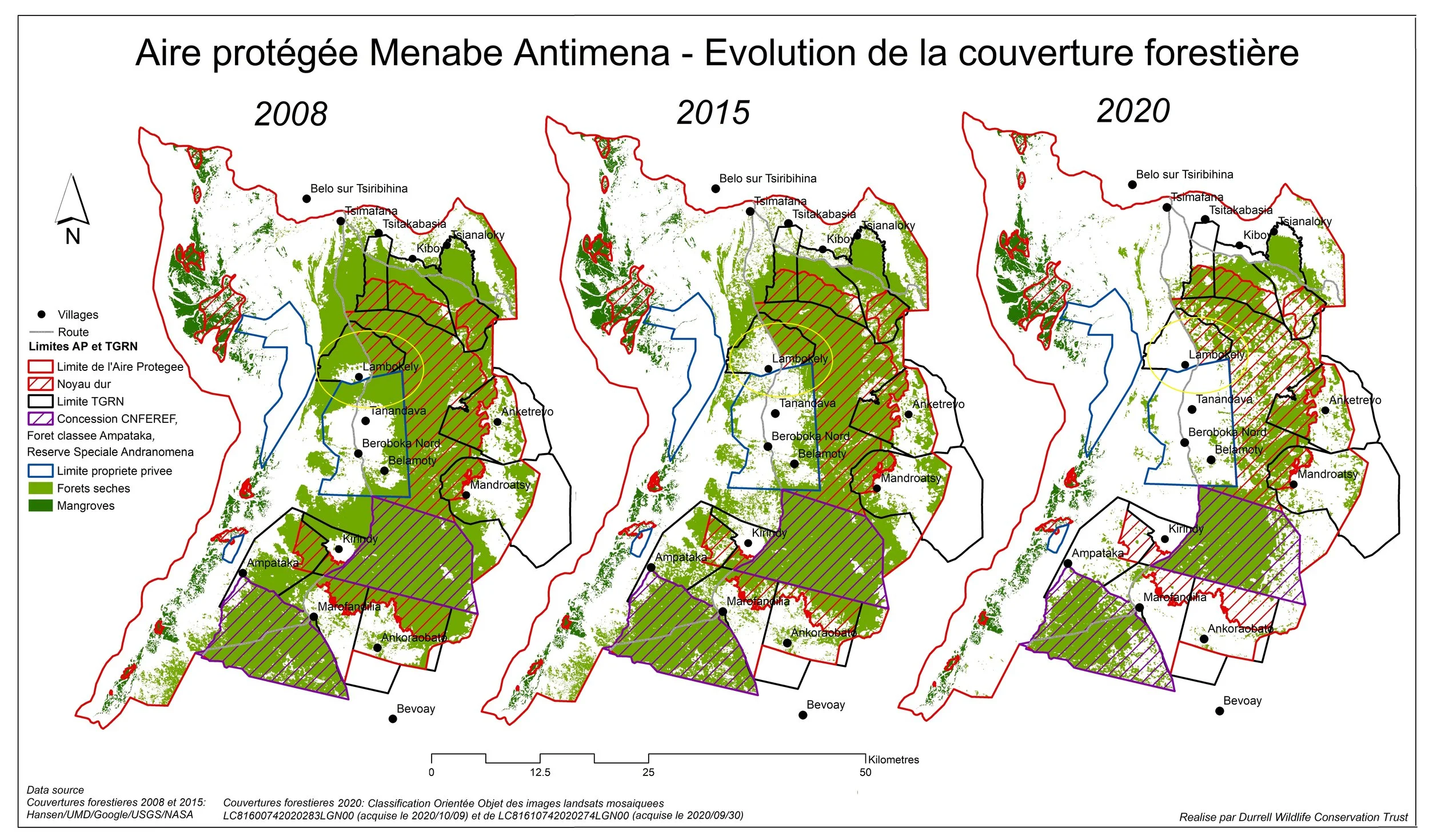

Forêt sèche de Menabe-Antimena : un écosystème très menacé. Source: DWCT Madagascar. (Le cercle jaune détermine la zone de Lambokely).

La culture sur brûlis persiste dans la zone de Lambokely et d'août à novembre, les défrichements illégaux et les feux de forêt font rage. Les acteurs de la conservation de la forêt protégée de Menabe-Antimena s’activent et multiplient les efforts pour atténuer les dégâts. Toutefois l’avenir de cette forêt sèche reste incertaine compte-tenu des potentiels effets socio-économiques de la crise du Covid19 et du changement climatique. Dans la région, la météo est de plus en plus imprévisible, les pluies sont irrégulières et faibles, et les températures augmentent. Ces effets risquent de s’aggraver avec la dégradation des terres dans cette zone. La stabilité des communautés locales qui y ont migré est donc à nouveau menacée.

Face à un tel contexte, Taniala Regenerative Camp se veut être proactif avec pour objectif de contribuer à l'arrêt du cercle vicieux déforestation-désertification-migration-déforestation grâce au renforcement de la résilience des communautés locales et de leur écosystème. L'approche adoptée s’inspire de la permaculture-design, elle intègre des pratiques d’agroécologie, d’agroforesterie, de récupération des eaux de pluie et de restauration écologique. Je présente ces concepts à Bendray et à ses amis en précisant qu’il est indispensable de prendre la forêt comme modèle. La forêt naturelle produit de grands arbres et des plantes alimentaires sans que nul n’ait besoin d’arroser, d'apporter des engrais, d'effectuer des traitements avec des produits phytosanitaires. Son sol est toujours couvert, elle est constituée d’un mélange d’arbres et d’autres plantes, elle abrite de la biodiversité jusqu’à son sol. Notre système de production doit se calquer sur la forêt. La résilience, c'est concilier production agricole et régénération d’écosystème.

Cette approche permet d’agir à différentes échelles allant d’un jardin à un paysage entier en passant par le niveau champ d’exploitation et communautaire. Nous avons commencé par l’installation de deux jardins potagers en permaculture dans la cour de Bendray et d’un autre ami. Ce qui se passe dans la forêt est reproduit à une échelle réduite grâce aux plates-bandes de ces jardins permagardens. Bendray et ses amis observent et apprennent. Ils comprennent l’importance de la matière organique ou de l’humus pour le sol grâce au paillage. Par l’association des cultures, ils apprennent l’importance de la biodiversité pour la résilience et l’optimisation de l’espace disponible. Ils ont été également initiés à la culture de plantes fertilisantes pour enrichir leur sol.

Actuellement notre pépinière est prête pour la production de différentes espèces d’arbres fruitiers et d'arbres fixateurs d’azote dans l’optique de les intégrer dans le système agricole local et pour nos futures forêts-jardin. L’arbre n'est pas notre ennemi à abattre, il est notre allié, il nourrit le sol et nous nourrit, nous les Hommes.

De telles actions locales sur le terrain sont à encourager et à développer dans le cadre du mouvement mondial pour la restauration des écosystèmes. La proximité de ces actions leur confère la qualité de catalyseur porteur de changement de comportement durable au sein des communautés. Rappelons-nous également d’une citation de l’anthropologue Margaret Mead « Ne doutez jamais qu’un petit groupe de citoyens engagés et réfléchis puisse changer le monde. En réalité, c’est toujours ce qui s’est passé». Avant de terminer, souhaitez-vous peut être me connaitre ? Je suis Tahina Roland Frédéric, jeune agronome forestier Malagasy et promoteur de l’initiative Taniala Regenerative Camp. Mes maîtres mots sont «communauté et sol vivant ». Le sol est au cœur de notre initiative car c’est lui la solution sous nos pieds. C’est tout simplement la « SOL-ution » pour l’humanité.

About

Tahina Roland Frédéric is a young Malagasy agronomist specializing in forestry. He is actively engaged in safeguarding his country's natural forests through strategies involving local communities. He is deeply committed to the conservation of the Menabe Antimena Protected Area, in his home region. Thanks to his diverse field experience, he has a prodigious knowledge of the institutional, socio-economic and ecological issues the dry forests in this Protected Area are up against. Tahina is well-versed when it comes to applying local, interdisciplinary and holistic approaches to the environmental field. In order to contribute to the mitigation of natural resource degradation in his country, he has co-created and is implementing the “Taniala Regenerative Camp” initiative. Through this initiative, Tahina aims to connect local communities with practitioners, scientists and other players involved in ecosystem restoration. His search for practical and accessible solutions led him to the methodology of permaculture design and inspired him to incorporate practices combining agricultural production and ecosystem regeneration, such as regenerative agriculture and syntropic agriculture. Inspired by a sense of accountability, Tahina plans to use his skills to introduce local Malagasy communities to resilience, ecosystem restoration and techniques assisting soil regeneration, and restoration of degraded land.