Last Thursday, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the long-awaited Special Report on Climate Change and Land (SRCCL). As a neutral scientific body that assesses current scientific knowledge on climate change, the IPCC put together this report following calls from governments in 2016. The SRCCL looks at how greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) contribute to the climate crisis in land-based ecosystems and in human land use activities. It links these issues it to global challenges like climate adaptation and climate mitigation, desertification, land degradation and food security. Additionally, it includes potential options and solutions to deal with these multifaceted problems.

The release of the SRCCL signals a crucial moment in the battle against climate change. It represents two major firsts in IPCC history: it is the first IPCC report in which the majority of authors (53%) are from developing countries, and it is the first IPCC report that comprehensively looks into the relationship between land and climate change. The former matters due to the importance of including and listening to voices from the scientific community in the countries most vulnerable to climate change. The latter matters because agriculture, forestry and other land-use activities contribute to around 23% of human greenhouse emissions. If pre-production and post-production activities within the global food system are included, it is estimated this overall figure could rise to 37%.

The summary for policymakers of the SRCCL, the source of the data and information discussed in this post, states that around one quarter of global ice-free land is degraded as a result of human activities, with climate change exacerbating this problem. Land degradation refers to a loss in the health, quality, efficiency and capacity of land. Climate change contributes to it through an increase in extreme weather conditions and environmental changes that harm land ecosystems, such as heatwaves, dry spells, heat stress, erratic rainfall patterns, flooding, droughts and sea-level rise. At the same time, land is not only a carbon sink (i.e. it removes and stores carbon from the atmosphere), but also a carbon source: unsustainable and harmful practices that degrade land lead to higher GHGs emissions.

The double-edged nature of land in the face of climate change presents a variety of interrelated environmental, social and economic challenges. For instance, let’s look at agriculture and food security. Resource intensive and large-scale agricultural systems, particularly those that include livestock, significantly contribute to land degradation and increased GHGs emissions, resulting in increased temperatures. This leads to climate change, with an increase in extreme weather events that result in natural disasters like flooding, which disrupt agricultural systems.

As a result, there is instability in food supply chains (i.e. food availability), leading to food shortages and/or higher food prices. With a limited (or non-existent) access to food and a nutritious diet, food insecurity, and hunger in vulnerable contexts, arise. Coupled with previous disruptions to agricultural livelihoods, all this brings about significant social and economic suffering, particularly for the poorest.

Whilst the above might seem an overly-alarming scenario, it is far from unrealistic. Just this summer, India has experienced a severe drought at an unprecedented level. Water scarcity and agricultural losses have led to mass displacements from rural areas, health challenges and economic hardship, as around 44% of the Indian population works in the agricultural sector. Moreover, even though these occurrences are more prominent and most felt in the Global South, the Global North doesn’t escape them. A couple of years ago, bad weather conditions in Spain resulted in vegetable shortages across British supermarkets, owed to short supplies and high prices. The Spanish region of Murcia, source of 80% of Europe’s fresh produce, was hit with its heaviest rainfall in three decades, rending two-thirds of its agricultural fields as unusable, and negatively impacting smallholder farmers and agricultural workers.

A dry river in India. [Source]

Despite all the concerns and issues highlighted, not all is doom and gloom. There is hope, including land-related actions that simultaneously tackle climate change, land degradation, desertification, food insecurity and sustainable development challenges. These actions, as described in the SRCCL, include:

· Sustainable forest management.

· Soil organic carbon management.

· Land ecosystem conservation and restoration.

· Reduced deforestation and land degradation.

· Sustainable food production systems.

· Reduced food loss and waste.

· Transition to balanced and more plant-based diets.

Whilst the above are all effective and important actions, their level of immediate impact varies. For instance, the conservation of land ecosystems rich in carbon, such as wetlands and mangroves, is more immediately effective than reforestation or the restoration of degraded lands. Indeed, it is better to prevent than to cure. This is because there are limits to the restoration and adaptation potential of certain natural environments. Coastal erosion owed to sea-level rise is one of such examples, as land often just disappears, with nothing left to restore. Additionally, actions that require converting land can lead to higher GHGs emissions, hence why it is better to improve the management of existing land.

Despite the existence of these solutions, some of which are already being implemented, none of the hope offered by these actions will materialise without higher ambition, commitments and actions. The SRCCL stresses the importance of collaborative, mutually supportive and multisectoral policies, as social, economic and environmental conditions shape the effectiveness of actions. There is also a need for both local/community action and national/international action. The sustainable local management of natural resources plays as much of a role as national reforms to land-related subsidies. Additionally, those most vulnerable to land degradation and climate change (particularly indigenous people, women, the marginalised and the poor) need to be better actively involved in policy-making.

“Through a boat expedition led by Doune Baba Dieye’s village chief, I learnt about the effects of the flooding disaster […]. When the sunken lands started to re-surge, tree-planting became key to prevent further coastal erosion. Additionally, by planting specific species that help with desalinization through their natural filtration properties, locals made sustainable organic orchards in the reappearing islets, growing vegetables like cabbage, watermelon and potatoes. ‘Artificial’ islets had also been created for migratory birds.” For the full story, check here. / Photos and text credit to Emily B. N’Dombaxe Dola.

Urgency is another key takeaway from the SRCCL. More ambitious action must happen promptly. The more action is delayed, the higher the risk for less effective interventions, more trade-offs, irreversible losses/degradation, and higher economic impacts and costs. Important short-term actions to be taken involve finance for land-related measures, risk management, early warning systems, filling implementation and up-scaling gaps, and knowledge-sharing.

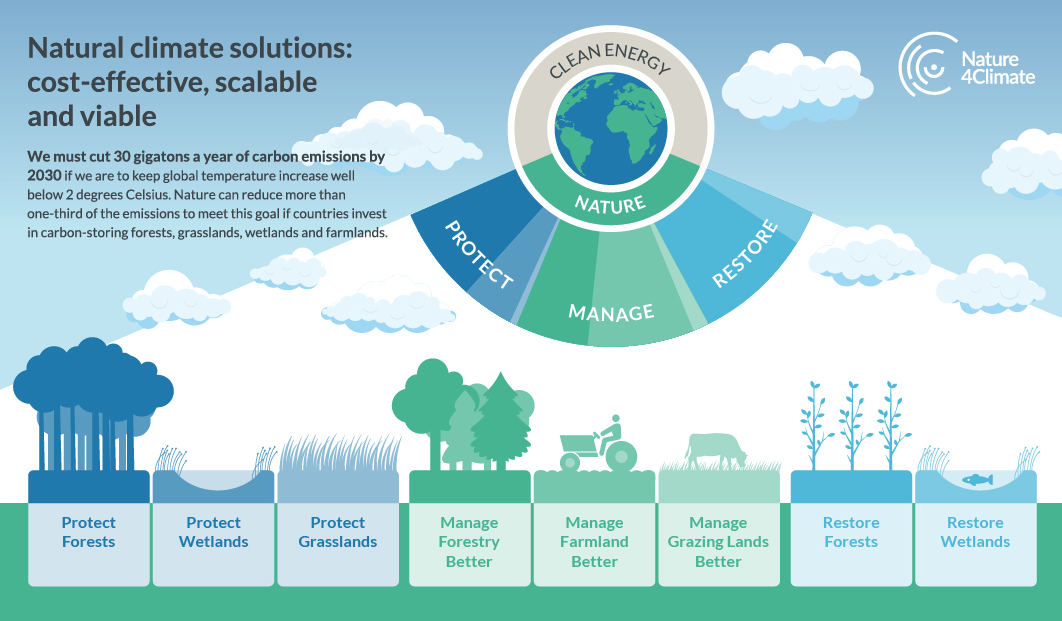

From a personal viewpoint, the IPCC’s SRCCL is both a reality check and a path to action. Land degradation and climate change are interwoven problems with social, environmental and economic implications and solutions. Each leads to the other, addressing each requires addressing the other. There lies the power of land-related actions, similarly also known as nature-based solutions (NBS), actions that conserve, manage and restore nature whilst simultaneously promoting biodiversity, human-wellbeing, mitigation, adaptation and resilience. Unfortunately, though essential to keeping temperature rise below 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, land-related actions/NBS are often ignored within climate negotiations, policy and financing.

Credit to Nature4Climate.

The SRCCL makes something really clear. Rather than focusing on only some solutions and ignoring others, there is a need to align and synergise diverse action. A just transition towards decarbonised societies needs to go together with transformational adaptation for resilient communities, and ecosystem protection and restoration. As originally envisioned by environmental justice groups and trade unions, just transition refers to a group of principles, processes and practices to fairly and justly move from an extractive to a regenerative economy, rectifying past damages and promoting equal relationships of power within societies. Equally as contested, transformational adaptation often refers to systemic long-term changes that consider social and economic justice.

It is hard to impossible to keep global temperature rise below 1.50C, to adapt to present, previewed, and unforeseen future impacts, and to address ongoing damage to ecosystems, without harmonsing and combining these areas of action. This is evident in the SRCCL. The report features different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (i.e. potential future scenarios according to actions taken), each of them with different results. The best-case scenario for effective mitigation and adaptation includes the stabilisation of/low population growth, higher incomes, reduced inequalities, effective land-use regulations, less resource-intensive production, low-GHG food systems, reduced food waste and loss, free trade, and environmentally-friendly technology and lifestyles.

Now, what happens if we discard certain actions, particularly socio-economic and systemic measures? As indicated in the SRCCL, the best-case scenario without high incomes and reduced inequalities leads to high challenges to achieve adaptation (as land-based ecosystems are already degraded, and will likely be further degraded). On the other hand, the best-case scenario with the current system of resource-intensive production, consumption and lifestyle results in high challenges to achieve mitigation (as land degradation and high GHGs emissions continue). This showcases why just transition, transformational adaptation and ecosystem protection and restoration go hand in hand: the three are vital to the best-scenario in the report. And, land-related actions/NBS, as envisioned by the SRCCL, can support action in these three areas simultaneously.

In essence, the IPCC’s SRCCL shines light on interlinked global challenges like climate adaptation and mitigation, desertification, land degradation and food security, whilst suggesting land-related actions/NBS that can mutually benefit all these areas. Whilst much of the current discussion misguidedly focuses on singular individual lifestyle changes, just like with the Special Report on 1.5C, we urgently need large-scale and context-dependent action that is participatory, inclusive, multi-sectoral, and actively considers ecological, social, economic, cultural and institutional factors. Our actions as individuals matter, as communities they are essential, but neither are enough. We must push governments to commit to meaningful and systemic action, we must hold high-emitting companies (both in the fossil fuel and land sectors) accountable. In recent months, children and youth across the world have made clear that they are ready to take up this challenge. So, when will the big players in the room?

Emily B. N’Dombaxe Dola is a Campaign Assistant for Youth4Nature. A BA in International Development graduate, she has a variety of experience in civil society organisations, campaigning and multi-sector projects. Emily is based in Brighton, UK.

![A dry river in India. [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d07cde0701969000168c986/1565550297001-VG2RKYR5LQUPYWIIKSKC/india-2714019_960_720.jpg)