From forgotten frontline communities to the world: the climate crisis from an Internal-Displaced-People perspective

This blog was created by a Youth4Nature team member after visiting a migrant camp in a country that is suffering from long-term war and an urgent climate/natural disaster. Due to safety concerns and security risks for both the writer and residents of the camp, we have chosen to maintain anonymity for the author as well as the name and location of the camp.

From the Foreign Minister of Tuvalu giving his COP26 address while standing in knee-deep seawater to “The Walk” of little Amal across Europe to stories like this one that we hear through our Y4N Storytelling Campaign, the impacts of displacement due to climate change are all around us. In fact, a recent article in Al Jazeera identified that “the number of new people forced to move within their own countries by climate disasters rose to the highest in at least a decade in 2020”.

While these numbers continue to grow and enter mainstream awareness, it is crucial that we also listen to and support those who have already been displaced - from political instability, economic insecurity, war, or other impacts - and consider the increased and intersectional risks that these communities face from climate change. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) states that “The impacts of climate change are numerous and may both trigger displacement and worsen living conditions or hamper return for those who have already been displaced.”

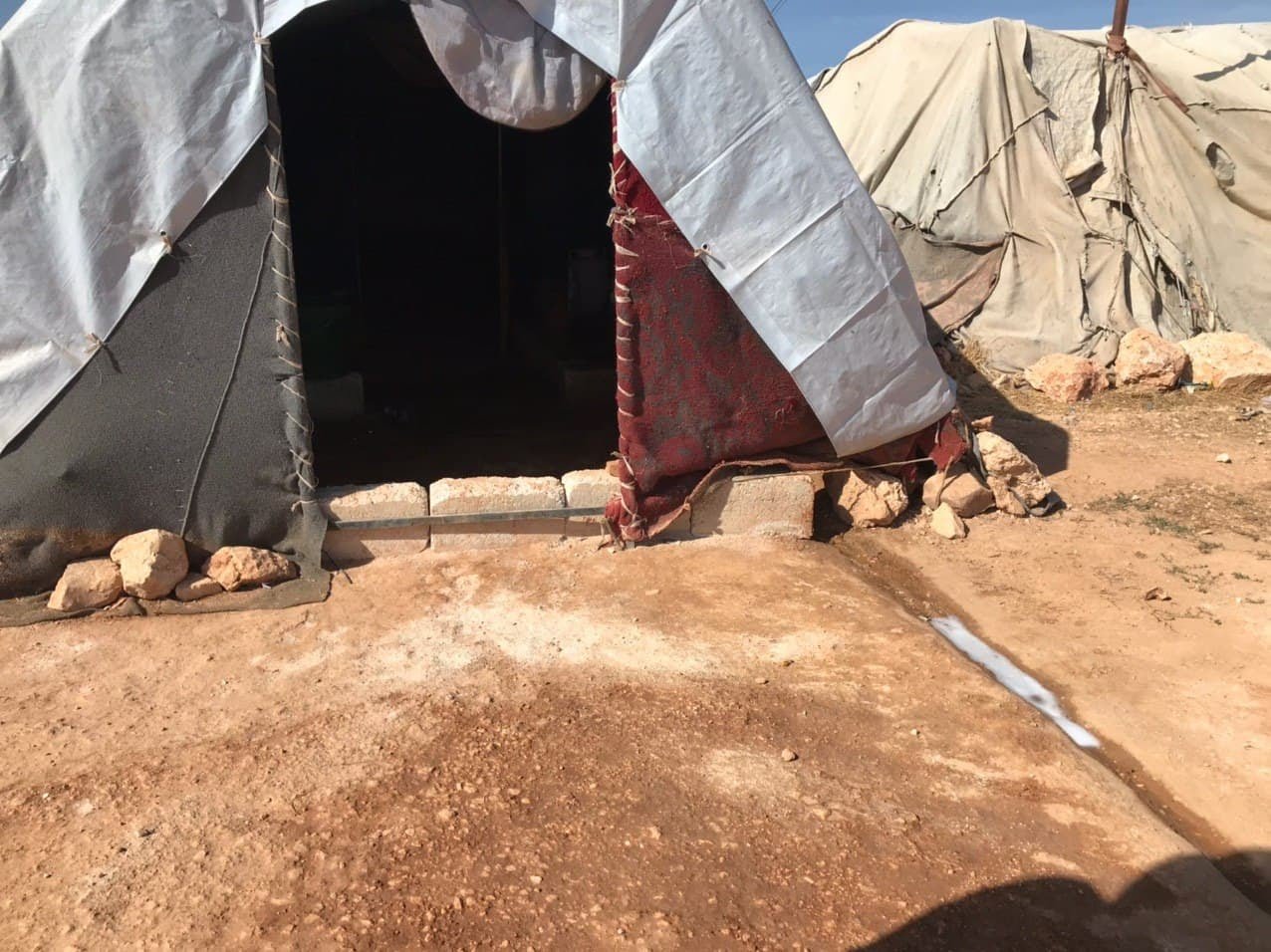

In this blog, a Y4N team member will take you to the frontlines, visiting a migrant camp in a war-torn country to share the stories of these residents and how they are experiencing and adapting to the impacts of climate change every day.

The residents of the camp we visited are predominantly Indigenous people. Only 1km from the fighting lines, they had been living there for more than 6 years. When we visited the camp, there were about 700 people, including 168 families.

Youth4Nature was not able to enter this camp as an international organization and without a lot of photographic reporting to not catch any attention from the party that is handling it. While there is currently a media blackout about all problems in this area, the Y4N team found alternative legal ways to access the camp with some young local support.

What are the climate change issues facing Internally Displaced People?

Internally Displaced People (IDPs) are people forced to move or flee their home within their recognized state borders because of the effects of conflicts, persecution, human rights violations, or natural disasters. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been mandated by the General Assembly of the United Nations to include IDPs in their responsibilities, even though they do not fit the standard “refugee” definition as it is a remaining grey area.

Of course, the impacts of climate change are different around the world and impact Internally Displaced People differently depending on the resources and infrastructure available for mitigation, adaptation, and relief. While not unique, here are some examples specific to the camp we visited:

The Extreme Weather:

“Storms are more common than before. Not just that, they are more powerful so that some tents weren't able to remain in the cold winters, keeping us without shelter, and causing a lot of health risks for our children while there is a very weak health system.” - Camp resident

Desertification:

The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the country where the camp we visited is located, mention that the forest cover has transformed from 32% of the country’s land at the beginning of the 20th century to less than 3% in 2016. This rapid desertification is applied at the same level on the agricultural lands, causing a fast increase in the cost of food crops, and putting more and more people into poverty and hunger.

Pollution:

As an area with very high waste leakage, many diseases are more common in this country. We met a woman that lost her child after he had cancer without any possible or accessible medical supply.

While there is an urgent need for medicines in countries facing armed conflicts, a lot of them are banned by Western laws to even receive these supplies. The lucky ones that do have access to these medicines are still not able to buy them because of their high price in comparison to the local wage.

How people are connecting with nature in the camp?

(3): A hand broom, created using spiny plants that are grown around the tents to protect it from dust and sand.

Without access to the internet or other technology, residents of this camp have one remaining resource to adapt to poverty and the climate crisis, a resource that they have had for thousands of years: nature.

Camp residents are trying to survive by planting seasonal and local vegetables and crops around their tents to help decrease the food scarcity that has been caused by the economic crisis that is threatening them. Additionally, they are planting some types of thistle plants for use as tent-hold cleaning equipment. (3)

An adaptation measure that can be defined as a nature-based solution (NbS), is the traditional way that the communities are raising animals. By using mud, straw, and limestone from the bottom of the wells to build fences and shelters for their livestock, this traditional process provides adequate ventilation and insulation for the sheep for free and without any processed materials.

Most of the people who have contributed to these NbS activities are women. This is important to note because, not only are women more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, but they are also leading on many of the solutions - even in the most challenging situations.

This traditional and local knowledge is not only crucial for their own survival but is important ecological information that could be used on a wider scale for local resilience building and climate adaptation. We must think about the knowledge and the knowledge holders!

What are young people in the camp are asking for from global decision-makers?

The main request that we heard from young people in this camp was a call to open the borders. Not just the physical borders between the west and them, but also the local and virtual borders that are created for political reasons by many colonising countries.

For example, in the country where this camp is located, there are laws that reject any type of financial interaction with local governments and private agencies. Additionally, all types of connections are cut between youth inside the country and the youth leaders globally who have more financial and educational support regarding climate change and global warming.

Having met the communities within the camp, Youth4Nature team members make their message loud and clear:

“We are asking for the very basics of justice. We are asking for a movement that does not exclude us. We are asking for free space to co-lead this movement from - this movement for safety, for human rights, for nature and climate, for our future.

This could be an intuitive right for young people from the wealthy countries who are trying to represent us, but sorry for you all, you cannot put yourself in my shoes, you cannot represent someone who was standing in the wells’ line to collect their families' water while you were striking your countries' parliament.

We are not asking for more discrimination in the youth climate advocacy action, we are really grateful for those folks who have sparked a very powerful movement. We need to be together on this work because diversity is always beneficial. We are asking the youth that do have the space, to make more space for more of us to join in.”

At Youth4Nature, we uphold this call to action from local youth and we call on you, reader, to do the same.

Additionally, as an organisation, we call upon youth leaders and state leaders to think of the system and work towards ending colonization and addressing all problems that it has caused and continues to cause today. We call upon decision-makers, governments, and institutions to provide unconditional and long-term funding to support both science and civil society action led by youth and front-line communities. We need more accessible and sustainable opportunities to join the conversation about our present and our future, and we need capacity-building opportunities led by our communities, for our communities so that when we do join the conversation, we can come prepared and ready to make an impact.

The bigger picture

While the 700 people in this camp are displaced because of the consequences of armed conflict, we cannot ignore an average of 25 million people who are displaced each year by natural disasters, the vast majority of which are climate-related (floods, droughts, hurricanes, etc.) and long term environmental changes (desertification, land degradation, rising sea levels).

Most migrations are internal movements of people inside the same country/region, making it difficult to have accurate estimated numbers of people being displaced.

According to the World Bank, 216 million people are at risk of internal displacement by 2050 if the Paris Agreement targets are not met and we stay on the current trajectory. These people will end up with the exact same future of suffering and daily pain as those we met in the IDP camps. This is why climate change is considered an important risk for international safety and stability, and its consequences are likely to lead to conflicts in the future.

While “environmental migration” is an adaptation strategy for most migrants (diversification of incomes, protecting themselves from climate disasters, lack of resources caused by an armed conflict…), the poorest and most vulnerable people without many resources, might not be able to use these strategies and adapt to being forced to suffer the most from climate emergencies. Investing in climate-related peace, by helping people who are living in the most climate change-affected areas, will be a better response for the developed countries than investing in building more borders.

In closing, though international law has not yet given human rights protection to people being forced to migrate because of climate, it should be a priority for young people in the climate movement to make sure that every single community is included in the discussion, and that we are using the power of multiculturalism to create more useful and accessible solutions that can help those people not just to adapt to the climate change consequences, but also to co-lead on the solutions with other young people around the world.

More photos from the camp we visited